THE TOWN of Porong lies 30 kilometers south of Surabaya, the coastal capital of East Java province in Indonesia. On the map, the town and the surrounding district of Sidoarjo is moored in a swath of rural green, part of the rice-growing countryside that nurtures Java, the most world’s most populous island. seen up-close, though, the Porong’s hinterland is semi-industrial farmland-a patchwork of backyard factories, rice paddies, shrimp farms and modern industrial buildings linked by toll-road to Surabaya.

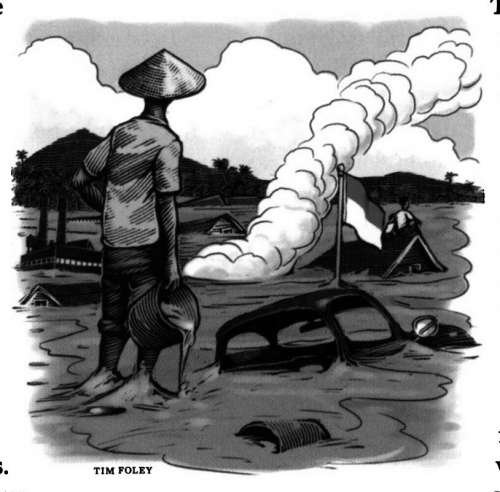

Since May 2006, the map has been redrawn in spectacular fashion. A volcanic outpouring of toxic mud has swallowed up 11 towns, engulfing homes, factories, schools and farms, and uprooting around 16,000 people. The mud covers 6.5 sq. kilometers, hemmed by a network of dams and levees. A 3 kilometer stretch of toll-road lies abandoned after a concrete bridge began to crack from subsidence. Trucks must crawl through Porong on a clogged two-lane street. And still the hot, stinking mud keeps gushing.

The disaster began with a wildcat well drilled by Lapindo Brantas, an energy company part-owned by Aburizal Bakrie, a prominent Indonesian tycoon and politician. The drilling opened a fissure in the ground from where the mud has flowed ever since. Efforts to staunch the flow have all failed, so engineers are pumping mud into the Porong River and out to sea, while shoring up the earthen dams. An eventual fix could be years away. In June 2007, Japan offered to build a 130-foot high dam around the volcano, on the theory that the dried, hardened mud would eventually cut off the flow.

Lying on the Pacific Ring of Fire, Indonesia is no stranger to natural disasters. Seizing on this seismic record, Lapindo executives sought to blame the Sidoarjo mudflow on an earthquake that hit Central Java three days earlier. Most geologists, however, reject this theory. Critics say it is part of a strategy by Lapindo to evade taking full responsibility for an expensive clean-up. So far, it seems to be working. Police in East Java have compiled a case against the company for criminal negligence, but prosecutors refuse to proceed, saying the evidence is inconclusive.

Yet for all its natural calamities-earthquakes, tsunamis, landslides-Indonesia’s real curse may lie in its boardrooms. A government tally of the economic cost of disasters in 2006 ranked the Sidoarjo mud volcano in second place, behind the deliberately-lit fires that annually ravage lowland forests on Sumatra and Borneo to make way for plantation crops. Both events amount to corporate malfeasance and environmental ruin hiding behind natural phenomena. The cruelest blow is to those who labor in the shadow of such willful destruction. Look no further than the entrepreneurs in Porong whose small family-owned factories-the lifeblood of Indonesia’s economy-lie buried in the oozing mud.

Indonesia is enjoying its fastest growth since the 1998 economic meltdown and fall of dictator Suharto. In retrospect, its bumpy transition to democracy now appears as a necessary learning curve that may be starting to pay off. Separatist conflicts no longer threaten the realm. Anticorruption agencies finally have teeth. Foreign investment is picking up, though not in labor-intensive manufacturing-the lure of China or Vietnam is stronger. Though government spending on education is still low, lawmakers have begun to address budgetary shortfalls.

But the family-run conglomerates that plundered and profited, then defaulted on their loans when the crisis hit, still play an outsized role in Indonesia, as they do across Southeast Asia. Many Indonesian firms have a lukewarm regard for corporate governance and pay little heed to reputational risk, reasoning that foreign capital will always be available. At least until the recent credit squeeze in the United States, that was a reasonable bet. Last year saw a flurry of new stock and bond issues by Indonesian borrowers with abysmal reputations, including Asia Pulp & Paper, which defaulted on a record $13.9 billion in debt in 2001. It seems that foreign investors have remarkably short memories when it comes to Indonesian conglomerates. For tycoons that despoil the environment, bilk minority shareholders and fund rent-seeking politicians, the future looks bright, particularly while commodity prices remain high.

Does this matter? Indonesia needs large companies capable of developing industries and providing services that the government can’t provide. It’s naive to expect that new entrepreneurs could replace overnight the disgraced leftovers of the Suharto era. Opaque corporate governance and corrupt regulators aren’t exclusive to Indonesia; foreign investors in China have their own horror stories to tell. But it’s easy to overlook such downside risks and focus on China’s domestic growth story and export prowess. China has also pushed its corporate giants to list on major international stock exchanges where regulations are stricter and minority shareholders expect disclosure. Few Indonesian companies seem willing or able to follow suit, preferring instead to do business in Indonesia’s malleable jurisdiction.

Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono has a solid economics team who has made smart macro decisions. Even the notoriously graft-ridden customs department has been put on its toes in recent months, and the judiciary may be next. But economic leadership needs to go further if Indonesia wants to promote a competitive system that rewards efficiency and innovation, not cartels and monopolies. In South Korea, the chaebol, or conglomerates, still exert an unhealthy influence over lawmakers, but they’ve proven that they can compete on the world stage. Few would dispute that corporate governance has improved in South Korea over the last decade, spurred by government regulators keen to cement their rise in the global economy.

By contrast, Indonesia’s corporate sector is similar to that of the Philippines: focused primarily on squeezing profits from domestic opportunities and lobbying to keep out competitors. In his book Asian Godfathers: Money and Power in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia, author Joe Studwell argues that economic success in the region has come despite, rather than because of, the outsized influence of its tycoons. He finds little to cheer in the region’s recovery since the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis, since the political elites apparently remain beholden to the same dominant players.

This business model doesn’t lend itself to global competitiveness. Boston Consulting Group released an annual ranking in December 2007 of the top 100 go-getting companies in developing economies. Not surprisingly, Indian and Chinese enterprises dominated the list. Indonesia, the world’s fourth-largest country, only managed one entry: instant noodle maker Indofood Sukses Makmur, part of the diversified Salim Group. Optimists point to the generational changes taking place in Southeast Asian conglomerates that are allowing Western-educated scions to take over the reins. This shift, coupled with regional economic integration, can be a force for good, if it means improving corporate governance and environmental practices.

But local regulators will still need to show teeth to increase the cost of noncompliance, as consumer activism-a key ingredient in shaping corporate behavior in the West-is lacking in Asia. Environmental campaigners in Indonesia have sought to close this gap by targeting careless resource companies, usually foreign investors such as U.S. mining companies, with limited success. In December, a district court in Jakarta rejected a lawsuit by Friends of the Earth Indonesia that sought damages against Lapindo and national and local government officials over their culpability in the Sidoarjo mudflow. The court ruled that it was a “natural disaster” and fined the plaintiffs a token amount.

Of course, many Southeast Asian conglomerates will choose not to go overseas because the returns are better at home. Opening up their markets to more foreign competition would force them to overhaul their model to stay ahead of the game. In turn, new entrants from more closely regulated economies will demand a level playing field, which should mean better corporate governance and less opaque regulatory systems. But without political will to tackle the most egregious abuses by influential companies, it’s hard to see how commercial agreements alone would be enough to shift behavior, since domestic interests usually trump trade relations. The strides made in South Korea on overhauling corporate governance and improving regulatory frameworks followed the election in 1997 of human-rights activist Kim Dae Jun. Globalization was a factor, but so was the determination of a newly elected leader to raise standards.

There’s another reason why Indonesia needs to clean up its corporate sector. Government inaction in the face of corporate abuses such as the Lapindo case does a disservice to the victims and, more broadly, to Indonesian voters. Unless politicians can hold wrongdoers to account-and make sure that taxpayers aren’t stiffed for the clean-up bill-it becomes harder to make the case for democracy as the cure for Indonesia’s ills. That would play to the gallery in much of Asia, where authoritarian governments are the norm and public participation is suppressed by “father-knows-best” rulers. With a presidential vote in Indonesia scheduled in 2009, a campaign by a strongman candidate who promises a firmer hand might be persuasive. That would be a setback for a democracy that is currently the most dynamic and decentralized in Southeast Asia, where voters are able to turf out local mayors who don’t cut it. Such a privilege is rare in the region.

Lapindo belongs to the Bakrie Group, a diversified conglomerate headed by Mr. Bakrie, 60. Its units include oil-palm plantations, mobile telecommunications, property and energy. Mr. Bakrie, who was ranked by Forbes in 2007 as Indonesia’s richest man with a net worth of $5.4 billion, is a senior executive of Golkar, the largest political party in Indonesia’s parliament. At the time of the accident, which he calls a “natural disaster,” he held the most senior economic post in President Yudhoyono’s cabinet. Lapindo tried to buy off homeless villagers with hand-outs as long as they signed waivers that exempted the company from lawsuits. When frustrated protesters from the accident site rallied in Jakarta to press for compensation and housing, Mr. Bakrie’s position appeared to be in doubt. But instead, when President Yudhoyono announced a reshuffle, his economics czar was moved to a new position: coordinating minister for public welfare.

To the families stuck in limbo in makeshift refugee camps in Porong, or living in rented rooms, that sounded like a cruel joke. Many have received cash hand-outs from Lapindo, but are waiting for full compensation for their loss of land, housing and livelihood. After months of dithering, President Yudhoyono issued a decree in 2007 that mandated the company to pay $412 million in compensation, including the purchase of despoiled land. But to the anger of would-be recipients, Lapindo insisted on paying 20% up-front, and the rest within two years. Sunarto, a businessman who goes by one name, says he refuses to accept the 20%, worth about $6,500 based on the value of his inundated family compound, which included a small cigarette factory that employed 40 workers. He wants the company to pay out now, so that villagers can rebuild their lives and plan for the future. “The local economy has collapsed… Even if you want to start a business, there’s nobody buying anything,” he said.

If a foreign oil company had triggered the mudflow, it might have been a different story. Pressure from shareholders and environmental activists, fanned by international news coverage, are a potent mix. But Bakrie calculated that it could hide behind the fiction of an unstoppable natural disaster and rely on its political clout to do the rest. From a bottom-line perspective, it was the right call. Taking full responsibility would have exposed the company to economic liabilities that are likely to run into billions of dollars, given the extent of the damage and the continued mudflow. Instead, Bakrie tried to arrange a fire sale of Lapindo, its part-owned unit, to obscure offshore investors for a nominal amount. However, Indonesia’s capital-markets regulator blocked the sale, which appeared to be a ploy to wash Bakrie’s hands of the toxic mud volcano. It was a shot by regulators across the bows of a local conglomerate, an all too rare sign that not all Indonesian institutions are cowed by their political masters.

Simon Montlake

© Far East Economic Review