In Indonesia, an entire district has been buried by an eruption of boiling, noxious mud. Was it a natural disaster-or an industrial accident?

On the morning of June 2, 2006, Ahmad Mudakir, a 33-year-old factory worker from Porong, a sleepy district in eastern Java, was in his front yard tinkering with his motorbike. A little after 8 a.m. he felt a rumbling in the ground-worrying, but not wholly unexpected in this seismically fitful corner of Indonesia. What happened next was anything but expected. Mudakir watched as a neighbor, who had been inside eating breakfast, came tumbling into the street. “There was an explosion,” Mudakir recalls. “Then the mud started to flow.” He gaped in amazement as a geyser of scalding sludge shot five meters into the air, collapsing the roof of his neighbor’s house. Mudakir froze. Then he gathered his mother and two brothers from inside his own house. “The whole village was panicking. Everyone ran.” Mudakir didn’t stop to collect his family’s belongings. He assumed he’d be able to return home.

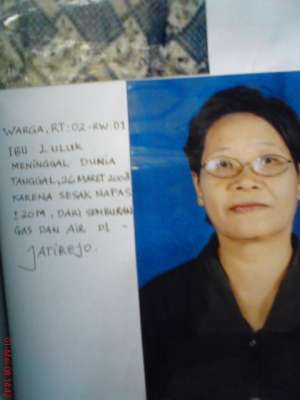

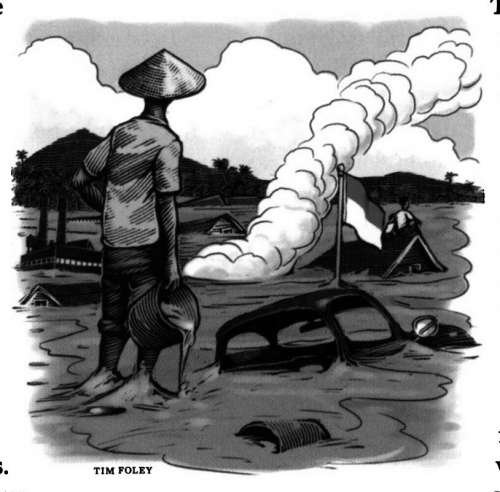

Today, Mudakir’s village, along with much of the rest of Porong, is gone, swallowed by an ash-gray lake of mud. The noxious sludge, incredibly, continues to flow at a rate of up to 5.3 million cu. ft. (150,000 cu m) a day-enough to fill 50 Olympic-sized swimming pools. In total, Porong has been smothered beneath nearly 3.5 billion cu. ft. (100 million cu m) of the stuff. The mud has buried 12 villages, displaced around 16,000 people and caused more than a dozen deaths. Porong hasn’t just been destroyed; it has been erased. Where Mudakir’s house once stood, there is now a vast, gurgling expanse, with only the occasional protruding tree branch or rooftop to suggest the landscape entombed beneath it.

Locals call it Lusi-a portmanteau of the Indonesian word for mud, lumpur, and the name of the nearest city, Sidoarjo. Lusi is a mud volcano, though that appellation is somewhat misleading. The mud is actually more like brackish water. And, unlike the igneous volcanoes that dot Indonesia’s countryside, the underground plumbing fueling Lusi is largely mysterious. Twenty-two months after it first erupted, Lusi remains the world’s most bewildering environmental disaster. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” says Richard Davies, a geologist at Britain’s Durham University and one of only a handful of experts on mud volcanoes. “It’s a scene, when you see it, you can only say, ‘Oh, my God, it’s a complete bloody mess.’”

The destruction is total. At the eruption’s epicenter-known to workers at the site as the Big Hole-a 100-ft. (30 m) plume of white smoke billows into the sky, obscuring the sun and spreading the sulfurous odor of rotting eggs. On a narrow causeway leading to the caldera, dozens of trucks idle in a queue, waiting to deliver soil for the massive earthworks meant to contain the mud. Already, they have transported more than 88 million cu. ft. (2.5 million cu m) of dirt to build eight miles (13 km) of levees around the site. Dozens of cranes work late into the evening piling the dirt atop bulwarks nearly 65 ft. (20 m) tall in places.

As the mud rises, so must the levees, but so far Lusi seems to be outpacing human engineering. Twice the earthworks have been breached-most recently on Jan. 4-flooding more houses. On Nov. 22, 2006, the weight of the soil ruptured a natural-gas pipeline, causing a massive fireball that incinerated 13 workers.

According to an International Monetary Fund estimate, Lusi has already cost Indonesia $3.7 billion in damage and damage control. And things are likely to get worse. As mud spews up from the ground, the area around the eruption is gradually sinking. Eventually, Porong could become a giant sucking wound in the Earth.

Ground Forces

INDONESIA IS BOTH BLESSED AND CURSED by geology. Volcanic ash contributes to the archipelago’s fecund soil. Yet eruptions periodically kill thousands. Indonesia is also rich in minerals and oil, exporting nearly half a million barrels a day. All told, the country’s buried wealth accounts for almost 30% of its total exports. But the same grinding geologic processes that make this wealth possible also bedevil Indonesia with disasters like the 2004 earthquake and tsunami that killed more than 160,000 people in Sumatra. Lusi is unlike any previous disaster, however. Unfolding in implacable slow motion, it has confounded Indonesian engineers and mystics alike. The mostly poor villagers who have lost homes and livelihoods to the mud complain that the response to the unfolding disaster has been equally sluggardly-a symptom, perhaps, of the fault lines in Indonesian society’s own unsettled foundations.

That’s because mud isn’t the only thing boiling over in Porong. Villagers displaced by the eruption blame the disaster on PT Lapindo Brantas, an Indonesian mining company drilling for natural gas in the area. Lapindo is partly controlled by the family of Aburizal Bakrie, Coordinating Minister for the People’s Welfare, one of Indonesia’s wealthiest men and an ally of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. Victims of the disaster say that a murky web of political influence and corporate fecklessness has blunted the official response to the mud eruption. “Everyone is suspicious,” says Mas Achmad Santosa, one of Indonesia’s most prominent environmental lawyers. “It’s a politically heavy case.”

Some independent geologists, including Davies, believe that Lapindo may have inadvertently roused the awesome force slumbering beneath Indonesia. “I’m 98% certain this was due to drilling,” he says. Davies, who visited Porong last year and has studied the eruption extensively, thinks he knows how that happened. On May 27, Lapindo’s Banjar Panji-1 well was operating in a field not far from Ahmad Mudakir’s village. The well’s target was a shelf of limestone some 9,800 ft. (3,000 m) below the surface. Lapindo’s drillers were searching for natural-gas deposits, but the well was exploratory. No one knew for certain the subterranean conditions beneath Porong. The drillers had reached about 9,300 ft. (2,800 m) when they noticed a drop in pressure inside the well.

Such a drop, called a loss of circulation, isn’t uncommon in gas drilling. It usually means that natural fractures inside the borehole are allowing drilling fluid to leak out. Lapindo’s engineers responded by pumping heavy drilling mud into the well to seal the cracks and restore pressure. Then they began to pull out the drill. Davies thinks that while they were removing the drill on the morning of May 28, they set off a massive “kick,” in which high-pressure water and gas from the surrounding rock flowed into, rather than out of, the borehole. To prevent a potentially dangerous blowout, the drillers shut vents at the surface, effectively corking the pressure inside the well. But it was too late. Water from a pressurized aquifer thousands of feet below the surface surged upward, picking up debris from a layer of mudstone as it did. Davies compares the effect to a bicycle pump. When the pump is sealed, the pressure is contained inside. But when it is allowed to escape, air comes rushing out. Lapindo’s drilling primed a natural pump, he believes. Unable to escape through the capped well, the water sought other avenues. At around 5 a.m. the following morning, the first eruption started in a rice paddy about 500 ft. (150 m) from the Banjar Panji-1 rig.

Banjar Panji-1 never should have gotten so out of control, according to Richard Swarbrick, a British expert on geological pressure and a consultant to oil companies. Usually, when drilling in geologically unstable areas, engineers install steel casing at greater depths, where the low density of the rock might allow fluid to escape from the borehole. In the event of a kick, the casing allows drillers to maintain the integrity of the well. Swarbrick, who has reviewed Lapindo’s drilling plan, says the company originally intended to install casing at depths of 3,500 ft., 4,500 ft. and 8,500 ft. (1,000 m, 1,400 m and 2,600 m). “The conventional well design in that sort of pressure environment would be to install casing,” Swarbrick says. Yet, either through oversight or because of technical problems, Lapindo did not case the hole to the planned depth. “For whatever reason, they weren’t following the plan,” Swarbrick says. “They had 5,000 feet of open hole. That’s taking one heck of a risk.”

The Nature Argument

LAPINDO SAYS ITS DRILLING PLAN WAS approved by the government. “The drilling process complied with mandatory regulations,” says company vice president Yuniwati Teryana. “We met the requirements.” Teryana offers another explanation for the eruption. Two days before Lusi started, a 6.3-magnitude earthquake shook the city of Yogyakarta, about 190 miles (300 km) to the west of Porong. Lapindo believes that the quake opened natural fractures that allowed the mud to escape. “The mud eruption is caused by a natural phenomenon,” Teryana says. That’s an opinion shared by Adriano Mazzini, a geologist at the University of Oslo.

After studying data provided by Lapindo, Mazzini concluded that Lusi was probably caused by the May 27 earthquake. “There is strong evidence for a naturally triggered event,” he says. Davies believes that if the eruption had been caused by the quake, it would have occurred sooner afterward; he cites research suggesting Porong was too far from the earthquake’s epicenter to be affected.

Given that no one fully understands the powerful subterranean engine powering Lusi, efforts to stop it have proven predictably ineffectual. Two relief wells intended to reduce pressure inside the original well have failed. Early last year, scientists from Indonesia’s Bandung Institute of Technology came up with a more novel idea: dropping thousands of concrete balls, linked with chains like a string of pearls, into the Big Hole. The idea was to bleed off pressure inside the volcano slowly enough so that Lusi wouldn’t simply erupt elsewhere-or shoot the concrete balls back out like a cannon. Satria Bijaksana, one of the Bandung scientists who came up with the idea, says that the balls reduced the mud’s flow temporarily. But the project was abandoned last March when a new government team took over management of the site. More recently, a Japanese team proposed building a 130-ft.-high (40 m high) dam to contain the mud. Scientists familiar with Lusi have dismissed that idea. Because the ground beneath the caldera is still sinking, a heavy concrete dam would likely rupture.

Going with the Flow

LUSI MAY, IN FACT, BE UNSTOPPABLE. IN 1979, the oil company Shell set off a similar eruption while drilling off the shore of Brunei. That mudflow took 20 years and 20 relief wells to halt, according to Mark Tingay, a geologist at the University of Adelaide in Australia. Lusi may eventually choke itself as mud clogs its interior plumbing. But if left to die on its own, Davies estimates that it could continue to erupt for years, and perhaps even decades. Hardi Prasetyo, deputy head of the new government team in charge of Lusi, says that his workers are now focusing on containing, rather than stopping, the mud. The current strategy includes channeling the sludge into the nearby Porong River in the hope that it will be flushed to the sea. Mud flows through a massive spillway to a pumping station, from which it gushes into the river. Two dredges work to keep the waterway open. But already, the river is filling with mud. At a shrimp farm downstream, where men stripped to their underpants wade through paddies, workers complain that the mud is clogging their water supply. “This is a war,” says Prasetyo, gesturing at a line of trucks rumbling along a levee. “We are not promising to stop it. We must also pray to God.”

Locals have turned to less orthodox methods. According to one popular story, the Lapindo drilling may have angered a spirit living in a tree near the eruption site. Such beliefs have an enduring appeal in this part of Indonesia, where religion is a syncretic mix of Islam and animism, and Lusi has drawn mystics from Bali and Borneo, who have sacrificed chickens, monkeys and even a cow to mollify the upset spirit. The government’s engineering team has tried similar tactics; a spokesman says the group has hired diviners to pray for rain to wash the mud away.

Along with the mystics have come opportunists. To attract curious visitors, one enterprising local hotel changed its name to Kuala Lumpur: “Lake of Mud.” In the roads near Lusi, shirtless men dart in and out of traffic selling bags of roasted nuts and dried fruit. They have also installed themselves at certain busy intersections, and demand a small levy to let cars pass. At the top of a levee, the men eagerly tout CDs compiled from video footage of the disaster. “Professional best,” promises one CD featuring a photo of a charred, mud-crusted corpse on its front cover. Some of the CD sellers are displaced villagers; others are merely hoping to make a little money. One man cheerfully says he is a pickpocket. For 10,000 rupiah, or about one dollar, the touts offer visitors motorbike tours of the site.

One, a laconic, mostly toothless man named Purwanto, says he was a farmer before the mud smothered his rice fields. He now makes extra cash taking tourists to the wreckage of his house, located in the shadow of the levees. Purwanto’s village flooded last year when the dikes broke, and, although it hasn’t been fully inundated yet, most of the people have demolished their homes for scrap and moved on. At present, the village looks like it has been carpet-bombed, with piles of rubble rising out of the greasy water. Purwanto points out an especially large mound: the remains of the town’s grandest house. His own more modest home is gone except for the broken stubble of the walls. “I was born at this house,” Purwanto says, sucking contemplatively on a clove-scented cigarette. From a nearby mosque, still being used despite the rising mud, the call of the muezzin echoes through the abandoned village. “Where my parents are buried is covered by the mud,” Purwanto adds.

There’s no question about whom the villagers blame for their distress. At a refugee camp in a local outdoor market, where more than 2,000 people live in converted, tarp-covered stalls amid goats grazing contentedly on piles of garbage, graffiti makes their target clear: “Lapindo terrorist,” one reads. The company provides food for everyone in the camp, along with services such as a medical clinic and a makeshift mosque. But the villagers are quick to recite a litany of complaints, from the quality of the rations to the health effects of the mud (though the government team says the gas coming from Lusi has no ill effect, locals complain of difficulty breathing and strange rashes).

Mostly, though, they complain about money. On the orders of the Indonesian government, Lapindo has agreed to compensate the villagers with a total of $412 million-the company is offering 20% of the money up front, with the balance paid within two years. “It will not be enough,” says Riati, a 45-year-old woman sitting outside the 16-ft.-wide (5 m wide) cubicle where she lives with her husband and sister. Riati says she turned down Lapindo’s offer of 40 million rupiah, or about $4,500-with an initial payment of 8 million rupiah-because she says even the full amount is not enough for her to buy a new home. Teryana, the Lapindo vice president, says the company hopes the holdout villagers can be persuaded to accept the compensation scheme.

Anger Management

AS NEGOTIATIONS HAVE DRAGGED ON, THE refugees are growing increasingly militant. In one corner of the market camp, villagers have stockpiled sharpened bamboo stakes-a defense against possible forced eviction. The villagers have also directed their anger at local officials regarded as allies of the company. At one recent protest, a crowd of about 200 people occupied a government compound to demand the resignation of a village chief. The demonstration began almost casually, with families picnicking or resting beneath the shade of a banyan tree. But tempers rose with the broiling midday heat. A squad of policemen armed with machine guns arrived and took up a position opposite the protesters.

“Please respect our suffering,” a man shouted through a loudspeaker. A scuffle broke out between police and protesters, and the policemen surged forward, kicking and pushing the scattering demonstrators. One of the protest’s leaders explained that the police had previously exercised restraint when dealing with them. “We carry out our protests in a peaceful manner,” he said. “We never have anarchy.” Then he added, for portentous effect: “Not yet.” The demonstrations are indeed growing more aggressive: on Feb. 19, villagers blockaded a main road in the Sidoarjo area to protest a new parliamentary report that concludes Lusi was a natural disaster.

Fueling the refugees’ anger is the fear that Lapindo will walk away from its promises. Last September, PT Energi Mega Persada, a company controlling 50% of the Lapindo drilling project and connected to Bakrie, the Indonesian Cabinet minister, attempted to unload Lapindo for $2 to a company based on the island of Jersey but owned by Bakrie’s family conglomerate.

When Indonesian financial regulators blocked that sale, Energi Mega tried to sell half the beleaguered Lapindo to the Freehold Group, registered in the British Virgin Islands. That deal also collapsed amid controversy. The attempted corporate reshuffling raised fears among many that Lapindo was preparing to declare bankruptcy, thus potentially allowing parent company Energi Mega Persada to evade any liability for Lusi. Lapindo says it is committed to compensating Lusi’s victims.

Critics say the government’s own response to the disaster has been muddy at best. “The government is not serious in its handling of the disposal of the mud or settling the social problems caused by the disaster,” says Sonny Keraf, Indonesia’s former Environment Minister and head of a parliamentary investigation into Lusi. “They are leaving the people to face the company when it should be acting as a bridge between them.” Keraf says that, while he believes Lapindo is acting in good faith, the government’s indecisiveness is blunting any sense of urgency. A yearlong police investigation into the eruption has resulted in no indictments or clear conclusions. “It’s all about politics,” says Ivan Valentina Ageung, head of legal affairs for the environmental group Walhi, referring to the disaster in general. Walhi sued Lapindo, alleging it was responsible for Lusi; that, as well as another lawsuit, were decided in favor of Lapindo. A spokesman for Yudhoyono denies that Bakrie’s connection to the administration has influenced the government’s response. Indeed, it was Yudhoyono who ordered Lapindo to compensate the displaced villagers.

But cleaning up Lusi’s mess won’t be easy. In a worrying sign, heavy rains in early January caused a breach in the levees, forcing more than a hundred families to evacuate. With the government’s attempts to stop or channel the mud faltering, and the tide rising by the day, the sludge that swallowed Porong could eventually threaten another quarter-million homes. Indonesia’s Big Hole only gets deeper.

Petter Ritter | © Time