SIDOARJO, EAST JAVA, May – Eight-month-old David should be a happy, healthy and active baby. He should be living in his family’s modest but comfortable home in Indonesia’s densely populated East Java. And along with his siblings and parents, he should have enough to eat. But how life should be and how life is for this family of environmental refugees are worlds apart.

The home David’s parents worked so hard to establish is buried under a putrid ocean of hot sludge that now stretches eight square kilometres across East Java. A refugee camp is home these days.

On Tuesday (EDS: May 29), it will be exactly one year since Indonesia’s “mud volcano” first erupted from the site of a gas exploration well, linked to one of Indonesia’s most powerful families, and part-owned by Australian company Santos.

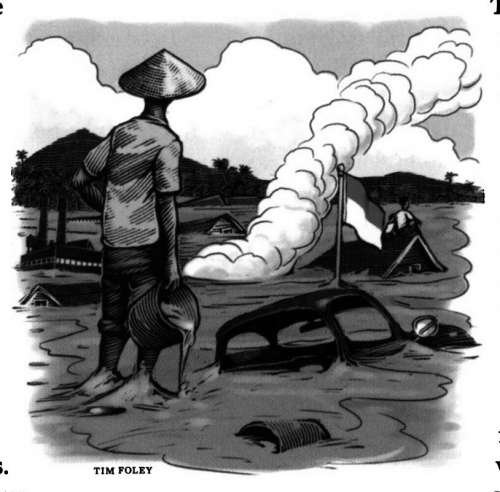

The seemingly unstoppable mud flow has spawned one of Indonesia’s biggest social and environmental disasters, with the thick brown sludge – 15 metres deep in parts – smothering nine villages, with thousands of houses, hectares of rice paddy fields, factories and mosques swallowed whole.

Its also been a political nightmare for Indonesia’s president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, whose Public Welfare Minister and one of Indonesia’s richest men, Aburizal Bakrie, is linked to Lapindo, the operator of the Banjar Panji well that was being drilled 3km underground when the mud first broke through the earth.

Police are investigating the company for negligence for allegedly not casing the well properly before drilling and have named 13 suspects, although it is unclear whether the case will ever make it to court.

Efforts to stop the mud – from magicians casting spells and tossing sacrificial bulls heads into the seething mess, to plunging 200kg chains of concrete balls down into the crater to try to plug the hole – have all failed.

Indeed, it shows no sign of slowing, with 160,000 cubic metres spewing from the crater every day – equivalent to 64 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Authorities are now focused on securing the cracked and leaking dirt embankments containing the mud, and trying to funnel it into a nearby river and eventually out to sea.

At the heart of the mess, the stench of sulphur chokes the air and only the hum of heavy machinery breaks the depressing silence of houses standing abandoned and decaying alongside dead trees.

Thousands of the 15,000 who lost their homes remain homeless, including 39-year-old Mujiati and her son David, who squat in a concrete shopfront within an large, vacant market centre, about a kilometre from the mud lakes.

“My baby is eight months old now, but he has lived here since he was two months old,” said Mujiati from Renokenongo, one of nine villages now buried by the mud.

“At that time, I didn’t have money to feed him so I had to use water from washing the rice to replace milk. The breast milk wouldn’t come so I didn’t know what else to give him. Sometimes I used steamed rice, boiled it with water and mixed it with banana to feed my baby. So now he is not that healthy, he lacks nutrition for development. He still cannot walk even though he is already eight months.”

The pair are among almost 3,000 people sheltering at the Pasar Baru Porong refugee camp after refusing to accept the compensation offered by the well’s operator Lapindo – a cash payment worth 20 per cent of the value of their house and land.

Mujiati has also lost her job after the factory she worked for was forced to close down. “Life here is hard. It has all been too sad and difficult for me,” she said. “We don’t eat regularly. We have already sold our bike for food. We have four kids, one wanted to continue his education but we cannot give him that. But I will remain here until they pay the compensation. Because of this mud, everything is destroyed. Whenever I see the mud, I feel something heavy in my chest. I lost my house because of that. It’s been swamped up to the roof.”

But the mud is not only an unfolding social and environmental tragedy, it has also become dangerous. Thirteen people were killed in November – most of them drowned – when a gas pipeline beneath the expanse of mud cracked and exploded under pressure.

Many fear a repeat of the accident, or worse, either from the partly-submerged electricity towers which dot the sinking landscape, or from the main railway line, which continues to run with mud lapping at the tracks. The land in the disaster area is sinking by about two to three centimetres a day, bending steel pipes, slowly sending houses crumbling and causing the levy banks halting the spread of the mudflow to crack and leak.

“At the time of the explosion, I was so panicked,” Mujiati said. “I was running around, holding my baby, confused about which way to go. “I just kept running barefoot, forgetting everything else to get my baby out of that mess.”

Authorities now appear to have switched their focus from trying to stop the flow, to containing it and funnelling it into the nearby Porong River, and eventually out to sea. A series of rusty pipes guide the mud into a holding pond where it is mixed with water to make it easier to pump, then funnelled into the nearby river.

But Soffian Hadi, of the Sidoarjo Mud Mitigation Team (BPPLS) overseeing the disaster said only “very little” had so far been dumped into the river, with the pumps frequently overheating.

He estimated about 0.3 cubic metres of mud was being pumped into the river per second, against 1.5 to 2 cubic metres flowing out of the crater. “I am embarrassed to tell you, because it is very small,” Hadi said.

Surabaya Institute of Technology expert Teguh Hariyanto estimated the “mud volcano” could spill up to 700 million cubic metres of mud before it stops naturally. “So far only 20 million cubic metres has spewed out, even though it is reaching it’s ‘birthday’,” he said.

Even the cause of the disaster is mired in controversy. Well operator Lapindo, with a 50 per cent stake, says the mudflow was triggered by a large earthquake hundreds of kilometres away.

Indonesia’s Public Welfare Minister Aburizal Bakrie, whose family controls the company that owns Lapindo, said the disaster had nothing to do with the drilling. “The experts which cover this thing in Jakarta, all over the world, have already said that it is not because of the Lapindo drill, but because of the earthquakes,” he told foreign press in Jakarta earlier this year.

The Bakrie group has reportedly already paid $US142 million ($A173 million) in compensation and mud containment efforts, and has been ordered by the president to pay a total 3.8 trillion rupiah ($A529.3 million).

Australia’s Santos, which has an 18 per cent stake in the well and has set aside $A89 million for its share, has refused to comment publicly on the likely cause.

The well’s third partner, Medco Energi, has openly accused Lapindo of gross negligence for not casing the well properly prior to drilling. It recently sold its 32 per cent share to a company backed by the Bakrie family group for the nominal sum of $US100 ($A122).

“I’ve never seen anything like that before,” Medco Energi chief executive officer Hilmi Panigoro told SBS Television recently. “We’ve seen blowouts, but I’ve never seen a blowout as big as this one. This is huge. We are talking about more than a million barrels a day of fluid coming out from the well bore and the area around it and that’s like production of oil from the whole of Indonesia.”

Santos won’t say whether it too is looking to sell its stake, but did say it remains “very concerned” about the ongoing challenges posed by the disaster, and the impact on the local community and economy.

“Santos continues to provide full and timely financial support to the response efforts, consistent with its 18 per cent share, and recognising the primacy of supporting those affected by the incident,” the company said in a statement. “An important priority remains ensuring that effective mud control measures are implemented so as to avoid further damage to property and infrastructure.”

But back in the Porong refugee camp, locals are growing increasingly frustrated and angry. Last week, some of the residents went on a hunger strike over the food provided to them, which they claim is inadequate and rotten.

Almost a third of those in the camp are infants or young children, who entertain themselves with homemade kites and board games. Twelve-year-old Desik said he longed to return home. “I don’t like living in this shelter,” he said. “It’s better at home. I don’t have to queue to take a shower, I don’t have to eat bad food. Everyday I see the mud and I feel sad because it drowned my house.”

At the disaster site, one or two women have set up makeshift stalls selling water and cigarettes to remedial workers. “My house is falling down, all the walls are cracked,” said Fatimah, 46. “I make a living here, because if I don’t do anything I am going to be stressed. I don’t go to the shelter because I am staying with my children. If I lived in the shelter, I would have to get up at four in the morning to shower, if not, I cannot shower because there will be a long queue already. It’s sad whenever I think about my house, but I am hoping to get the 20 per cent compensation. But it hasn’t come yet. I don’t mind that they are only giving 20 per cent as long as they give it soon.”

Fatimah said she was forced to flee her tiny shop recently when one of the dirt embankments built to contain the mud flow began to leak. “I just grabbed the money in the drawer and took the cigarettes and went quick,” she said. “Just like at the time of explosion, I ran as fast as I could.”

But ultimately there can be no running away for most of the people worst affected by the disaster. Many have nothing left and until the compensation comes, they have only one choice. To stay.

Karen Michelmore and Olivia Rondonuwu

© AAP News Wire